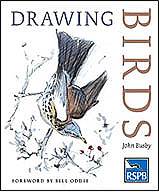

Forlagets egen omtale:

This is a fully revised and updated new version of a popular RSPB handbook to the art and joy of drawing birds. John Busby beautifully conveys his own remarkable ability to capture the grace and motion of living birds, illustrating his ideas and suggestions with many examples of his own work.

He also uses illustrations from over 45 other talented bird artists to demonstrate a variety of principles and techniques. The text covers a wealth of topics, including choice of media, sketching from life, composition and different ways of interpreting the subject matter. This is a beautiful and inspiring book which will appeal to aspiring artists and anyone who has ever been entranced by the beauty of birds.

Throughout the ages, whenever artists have made images from nature, birds have caught the imagination and inspired a creative response. They are seen as both beautiful and sinister, glorious in plumage but hard of eye and wild of spirit; as a quarry to be hunted for food and as inhabitants of the world of air, symbols of freedom beyond human reach. They have been made into the likenesses of gods, and fashioned into heraldic and national emblems of power. Even the invisible forces of good and evil have been given form as white dove and night-backed raven. In themselves birds are beautiful in form and movement, and so superbly decorative that they appear as motifs on all manner of ornament from pottery to postage stamps, tapestry to tableware, all over the world.

Plumage pattern is one of the richest veins in all nature, variety beyond anything artists can imagine for themselves. However, plumage detail in a painting only rings true in art when it is one with the vitality of the whole bird.

Bird painting was part of the culture of early China and Japan. According to Hseih Ho the 6th-century Chinese master, vitality was the first and highest of the six principles of painting.1 To the artists of the Far East, painting was an act of celebration as well as decoration. Peacock, pigeon, finch and crane are painted with a rhythmic grace and energy to match their character and keep them in harmony with their surroundings.

In the west, nature painting emerged only slowly as background detail to great religious and secular themes. Artists for the most part found wild birds too elusive to ‘capture’ in paint and, unless they confined themselves to tame species or made imaginative guesses about those they saw only fleetingly, the only recourse for many was to paint from dead birds. This practice led to rather static poses where a bird was painted as part of the quest for knowledge of species classification. The early scientist-artists who illustrated their own studies, made accurate rather than freely artistic paintings of birds. Often with great artistry, but sometimes with little knowledge of the living bird, they recorded details of a bird’s plumage. Although the paintings are often naive or quaint, and owe most to a museum specimen, the etching process and subsequent hand-colouring gave these early book plates an attractive clarity lost in many modern illustrations.

Today, with the aid of binoculars and telescopes, we can see wild birds with an intimacy undreamed of in the past, and we can watch behaviour that is unaffected by the fear of close human presence. This has opened up tremendous pictorial possibilities, and our understanding of behaviour has been enhanced by ornithological research. Yet, for some artists the ‘definitive study’ seems to dominate all other concepts of bird portraiture, to such an extent that an artist can be trapped creatively by the sheer weight of known facts by which he or she thinks the ‘rightness’ of a picture will be judged.

Correctness can become an obsession, and in some pictures one can imagine the artist ticking on a checklist of detail to be included before a bird can be considered finished. This is a formidable inhibition; one that can make a beginner doubt his or her own observation and suppress original creative ideas.

Artists also have a tendency to idealise nature and pander to patrons who like nature-art to represent perfection, just as flattery is often preferred in human portraits. However, birds in less than their full spring plumage are just as interesting as the immaculate specimen.